Authority of Scripture

“All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work.” (2 Tim. 3:16-17)

2 Peter 3:16

And consider that the longsuffering of our Lord is salvation—as also our beloved brother Paul, according to the wisdom given to him, has written to you, as also in all his epistles, speaking in them of these things, in which are some things hard to understand, which untaught and unstable people twist to their own destruction, as they do also the rest of the Scriptures.

Regarding Wisdom:

We have spoken of its beauty, and proved it by the witness of Scripture. It remains to show on the authority of Scripture that there can be no fellowship between it and vice, but that it has an inseparable union with the rest of the virtues. “It has a spirit sagacious, undefiled, sure, holy, loving what is good, quick, that never forbids a kindness, kind, steadfast, free from care, having all power, overseeing all things.” And again: “She teacheth temperance and justice and virtue.” – St. Ambrose (On the Duties of the Clergy, Book II, Chapter XIII)

Let them learn that we teach by authority of the Scriptures; for it is written: “For in Wisdom is a Spirit of understanding, holy, one only, manifold, subtle, easy to move, eloquent, undefiled.” The Scripture says He is undefiled, has it lied concerning the Son, that you should believe it to have lied concerning the Spirit? For the prophet said in the same place concerning Wisdom, that nothing that defiles enters into her. She herself is undefiled, and her Spirit is undefiled. Therefore if the Spirit have not sin, He is God. – St. Ambrose (On the Holy Spirit)

Heaven is of the world, man above the world; for the former is a portion of the world, the latter is an inhabitant of Paradise, and the possession of Christ. Heaven is thought to be undecaying, yet it passes away; man is deemed to be incorruptible, yet he puts on incorruption; the fashion of the first perishes, the latter rises again as being immortal; yet the hands of the Lord, according to the authority of Scripture, formed them both. For as we read of the heavens, And the heavens are the work of Thy hands; so also man says, Thy hands have made me and fashioned me; and again, The heavens declare the glory of God. – St. Ambrose (Letter XLIII)

Vainly then do they run about with the pretext that they have demanded Councils for the faith’s sake, for divine Scripture is sufficient above all things ; but if a Council be needed on the point, there are the authoritative acts of the Nicene Fathers, for they did not do their work carelessly, but stated the doctrine so exactly, that persons reading their words honestly, cannot but find their memory refreshed in respect to the pious doctrine concerning Christ announced in divine Scripture. – St. Athanasius

‘The holy and Divine Scriptures are sufficient of themselves for the preaching of the truth.’ – St. Athanasius

St. Theophilus of Alexandria – Quoted from Theophilus of Alexandria by Norman Russel, Originest Controversy

For my part, I cannot understand by what temerity Origen invents such things, and follows his own error rather than the authority of the Scriptures, or how he could have the audacity to publish things potentially harmful to everyone. He does not reckon that there will ever be anyone who will oppose his assertions, if he mixes the subtlety of the philosophers with his own arguments, and advancing from an evil beginning to certain fables and lunacies, turns Christian doctrine into a game and a farce. He does not rely on the truth of divine teaching at all, but on the judgement of the human mind. He swells with such pride at being his own teacher that he does not imitate the humility of Paul, who, though filled with the Holy Spirit, took counsel on the Gospel with the leading apostles, for fear he should be running or had run in vain (cf. Gal. 2:2). He does not know that it is an impulse of a demonic spirit to follow the sophisms of human minds and reckon anything outside the authority of the Scriptures as divine.

The Scripture being of itself so deep and profound, all men do not understand it in one and the same sense, but so many men, so many opinions almost may be gathered out of it; for Novatian expounds it one way, Photinus in another, Sabellius in another, Donatus in another. Yet otherwise do Arius, Eunomius, Macedonius expound ; otherwise Photinus, Apollinaris, Priscillianus; otherwise, lastly, Nestorius. But then it is therefore very necessary, on account of such exceeding varieties of such grievous error, that the line of Apostolic and Prophetic interpretation be guided according to the rule of the Ecclesiastical and Catholic sense. – St. Athanasius

The holy and inspired Scriptures are sufficient of themselves for the preaching of the truth; yet there are also many treatises of our blessed teachers composed for this purpose. contr. Gent. init.

For studying and mastering the Scriptures, there is need of a good life and a pure soul, and virtue according to Christ,” Incarn. 57.

” The Scriptures are sufficient for teaching; but it is good for us to exhort each other in the faith, and to refresh each other with discourses.” Vit. S. Ant. 16.

“Do not believe me, let Scripture be recited. I do not say of myself, ‘In the beginning was the Word,’ but I hear it; I do not invent, but I read; what we all read, but not all understand.” Ambros. de Incarn. 14.

“That it is the tradition of the Fathers is not the whole of our case; for they too followed the meaning of Scripture, starting from the testimonies, which just now we laid before you from Scripture.” Basil de Sp. S. n. 16. vid.

The authority of Scripture seemed to me all the more revered and worthy of devout belief because, although it was visible for all to read, it reserved the full majesty of its secret wisdom within its spiritual profundity. While it stooped to all in the great plainness of its language and simplicity of style, it yet required the closest attention of the most serious-minded–so that it might receive all into its common bosom, and direct some few through its narrow passages toward thee, yet many more than would have been the case had there not been in it such a lofty authority, which nevertheless allured multitudes to its bosom by its holy humility – St. Augustine (Confessions)

I desire you therefore, in the first place, to hold fast this as the fundamental principle in the present discussion, that our Lord Jesus Christ has appointed to us a “light yoke” and an “easy burden,” as He declares in the Gospel: in accordance with which He has bound His people under the new dispensation together in fellowship by sacraments, which are in number very few, in observance most easy, and in significance most excellent, as baptism solemnized in the name of the Trinity, the communion of His body and blood, and such other things as are prescribed in the canonical Scriptures, with the exception of those enactments which were a yoke of bondage to God’s ancient people, suited to their state of heart and to the times of the prophets, and which are found in the five books of Moses. As to those other things which we hold on the authority, not of Scripture, but of tradition, and which are observed throughout the whole world, it may be understood that they are held as approved and instituted either by the apostles themselves, or by plenary Councils, whose authority in the Church is most useful, e.g. the annual commemoration, by special solemnities, of the Lord’s passion, resurrection, and ascension, and of the descent of the Holy Spirit from heaven, and whatever else is in like manner observed by the whole Church wherever it has been established. – St. Augustine (Letter to Januarius)

St. Basil of Ceaserea – De Spiritu Sancto, Chapter XXVII

Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or publicly enjoined which are preserved in the Church some we possess derived from written teaching; others we have received delivered to us “in a mystery” by the tradition of the apostles; and both of these in relation to true religion have the same force. And these no one will gainsay;—no one, at all events, who is even moderately versed in the institutions of the Church. For were we to attempt to reject such customs as have no written authority, on the ground that the importance they possess is small, we should unintentionally injure the Gospel in its very vitals; or, rather, should make our public definition a mere phrase and nothing more. For instance, to take the first and most general example, who is thence who has taught us in writing to sign with the sign of the cross those who have trusted in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ? What writing has taught us to turn to the East at the prayer? Which of the saints has left us in writing the words of the invocation at the displaying of the bread of the Eucharist and the cup of blessing? For we are not, as is well known, content with what the apostle or the Gospel has recorded, but both in preface and conclusion we add other words as being of great importance to the validity of the ministry, and these we derive from unwritten teaching. Moreover we bless the water of baptism and the oil of the chrism, and besides this the catechumen who is being baptized. On what written authority do we do this? Is not our authority silent and mystical tradition? Nay, by what written word is the anointing of oil itself taught? And whence comes the custom of baptizing thrice? And as to the other customs of baptism from what Scripture do we derive the renunciation of Satan and his angels? Does not this come from that unpublished and secret teaching which our fathers guarded in a silence out of the reach of curious meddling and inquisitive investigation? Well had they learnt the lesson that the awful dignity of the mysteries is best preserved by silence. What the uninitiated are not even allowed to look at was hardly likely to be publicly paraded about in written documents. What was the meaning of the mighty Moses in not making all the parts of the tabernacle open to every one?..In the same manner the Apostles and Fathers who laid down laws for the Church from the beginning thus guarded the awful dignity of the mysteries in secrecy and silence, for what is bruited abroad random among the common folk is no mystery at all. This is the reason for our tradition of unwritten precepts and practices, that the knowledge of our dogmas may not become neglected and contemned by the multitude through familiarity. “Dogma” and “Kerugma” are two distinct things; the former is observed in silence; the latter is proclaimed to all the world. One form of this silence is the obscurity employed in Scripture, which makes the meaning of “dogmas” difficult to be understood for the very advantage of the reader: Thus we all look to the East at our prayers, but few of us know that we are seeking our own old country, Paradise, which God planted in Eden in the East. We pray standing, on the first day of the week, but we do not all know the reason. On the day of the resurrection (or “standing again” Grk. ἀνάστασις) we remind ourselves of the grace given to us by standing at prayer, not only because we rose with Christ, and are bound to “seek those things which are above,” but because the day seems to us to be in some sense an image of the age which we expect, wherefore, though it is the beginning of days, it is not called by Moses first, but one. For he says “There was evening, and there was morning, one day,” as though the same day often recurred. Now “one” and “eighth” are the same, in itself distinctly indicating that really “one” and “eighth” of which the Psalmist makes mention in certain titles of the Psalms, the state which follows after this present time, the day which knows no waning or eventide, and no successor, that age which endeth not or groweth old. Of necessity, then, the church teaches her own foster children to offer their prayers on that day standing, to the end that through continual reminder of the endless life we may not neglect to make provision for our removal thither. Moreover all Pentecost is a reminder of the resurrection expected in the age to come. For that one and first day, if seven times multiplied by seven, completes the seven weeks of the holy Pentecost; for, beginning at the first, Pentecost ends with the same, making fifty revolutions through the like intervening days. And so it is a likeness of eternity, beginning as it does and ending, as in a circling course, at the same point. On this day the rules of the church have educated us to prefer the upright attitude of prayer, for by their plain reminder they, as it were, make our mind to dwell no longer in the present but in the future. Moreover every time we fall upon our knees and rise from off them we shew by the very deed that by our sin we fell down to earth, and by the loving kindness of our Creator were called back to heaven.

But this example may be an idle one as being derived from a human circumstance; I will take another, which has the authority of Scripture itself. It says that “God made man of the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living soul.” Now, although it here mentions the nostrils, it does not say that they were made by God; so again it speaks of skin and bones, and flesh and eyes, and sweat and blood, in subsequent passages, and yet it never intimated that they had been created by God. – Tertuallian (Against Hermogenes)

Why, then, should we hesitate to say what Scripture does not shrink from declaring? Why shall the truth of faith hesitate in that wherein the authority of Scripture has never hesitated? For, behold, Hosea the prophet says in the person of the Father: “I will not now save them by bow, nor by horses, nor by horsemen; but I will save them by the Lord their God.” If God says that He saves by God, still God does not save except by Christ. Why, then, should man hesitate to call Christ God, when he observes that He is declared to be God by the Father according to the Scriptures? – Novation (Concerning the Trinity, Chapter 12)

Let us now ascertain how those statements which we have advanced are supported by the authority of holy Scripture. The Apostle Paul says, that the only-begotten Son is the “image of the invisible God,” and “the first-born of every creature.” And when writing to the Hebrews, he says of Him that He is “the brightness of His glory, and the express image of His person.” Now, we find in the treatise called the Wisdom of Solomon the following description of the wisdom of God: “For she is the breath of the power of God, and the purest efflux of the glory of the Almighty.” – Origen (ORIGEN DE PRINCIPIIS)

On Scripture Canon

- There is evidence that early Christians already considered the writings of St. Paul “scripture” as early as 131 A.D. This is less than 30 years after the Apostle John died.

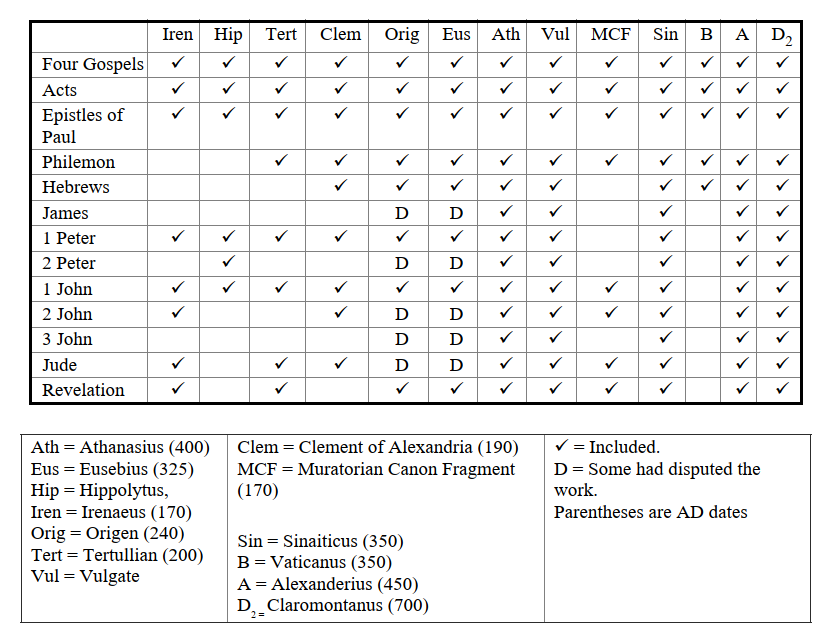

- An enumeration/canon of New Testament scripture was already in place by 200A.D . in opposition to Marcion. This list had 22 of the current books of the NT, and considered them scripture.

The earliest designation of a passage from the Gospels as “Scripture” was about 131, by the so-called Barnabas, and of a quotation from Paul about 110-117, by Polycarp. By the time of Justin (153), the Gospels were read in the services in Rome, together with the Old Testament prophets. The process by which the New Testament writings came to Scriptural authority seems to have been one of analogy. The Old Testament was everywhere regarded as divinely authoritative. Christians could think no less of their own fundamental books. The question was an open one, however, as to which were the canonical writings. Works like Hermas and Barnabas were read in churches. An authoritative list was desirable. Marcion had prepared such a canon for his followers. A similar enumeration was gradually formed, probably in Rome, by the Catholic party. Apparently the Gospels were the first to gain complete recognition, then the letters of Paul. By about 200, according to the witness of the Muratorian fragment, Western Christendom had a New Testament canon embracing Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Acts, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Galatians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, Romans, Philemon, Titus, 1 and 2 Timothy, Jude, 1 and 2 John, Revelation, and the so-called Apocalypse of Peter. In the Orient the development of a canon was not quite so rapid. Certain books, like Hebrews and Revelation were disputed. The whole process of canonical development into its precise present form was not completed in the West till 400, and in the East till even later. By the year 200 the church of the western portion of the empire had, therefore, an authoritative collection of New Testament books, in the main like our own, to which to appeal. The East was not much behind. The formation of the canon was essentially a process of selection from the whole mass of Christian literature, made originally by no council, but by the force of Christian opinion—the criterion being that the books accepted were believed to be either the work of an Apostle or of the immediate disciple of an Apostle, and thus to represent apostolic teaching. – Williston Walker (A History of the Christian Church, P. 62)

” Let the reader, standing in the midst on a raised space, read the Books of Moses, and of Joshua the son of Nun, those ot

Judges and of Kingdoms, those of Chronicles and the Return from Captivity [Ezra and Nehemiah] ; in addition to these those of Job and of Solomon and of the sixteen Prophets . . . After this let our Acts [Acts of Apostles] be read and the Epistles of Paul our fellow worker, which he enjoined on the churches according to the guidance of the Holy Spirit; and after these let a deacon or presbyter read the Gospels which we, Matthew and John, delivered to you, and those which Luke and Mark, Paul’s fellow-workers, received and left to you.” – Apostolic Constitutions

In announcing the books to be included in the formal New Testament Canon, St. Athanasius explained that these books were already “handed down, and accredited as Divine”:

It seemed good to me also, having been urged thereto by true brethren, and having learned from the beginning, to set before you the books included in the Canon, and handed down, and accredited as Divine; to the end that any one who has fallen into error may condemn those who have led him astray; and that he who has continued steadfast in purity may again rejoice, having these things brought to his remembrance.- St. Athanasius (Festal Letter 39)

The determination of the Canon of the New Testament was not the result of any pronouncement, either by an official of the Church or by an ecclesiastical body. Rather, the Canon was determined by the use of these books throughout all of the Churches during the first and second centuries. The establishment of the Canon was the process by which formal recognition was given to the writings of Scripture already recognized as authoritative. An early list of the books of the New Testament (A.D 170) appears in the Muratorian fragment, found by L. A. Muratori in manuscript form and published in 1740. Although the fragment is mutilated, it attests to the widespread use as Scripture of all books of the New Testament except Hebrews, James, I and II Peter. In A.D. 230, Origen (A.D.185-254) stated that all Christians acknowledged as Scripture the four Gospels, Acts, the thirteen epistles of St. Paul, I Peter, I John, and Revelation. He added that the following were disputed by some people: Hebrews, II Peter, II John, III John, James, Jude, the Epistle of Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Didache, and the Gospel according to the Hebrews. By A.D. 300, all the New Testament books we presently use were generally accepted in the churches, and by A.D. 367, Pope Athanasius listed all the 27 books as canonical in his Easter Letter, which form the New Testament as we have it today. In some areas, Revelation remained still under dispute as conducive to the heresies defeated at Nicea. — Sunday School Curriculum if the Coptic Orthodox Diocese of Southern USA , Grade 9

“I have learned from tradition about the four gospels that they alone are to be accepted without question in all the churches of God under heaven. For thus have the fathers handed down: that first of all Matthew, who had been a tax-collector, wrote a gospel in Hebrew script which was handed on to those from the circumcision who had believed; that the second was written by Mark in accordance with what Peter had handed on to him; he mentions him in his letter when he says, ‘My son Mark greets you.’ The third is according to Luke, and is commended by the apostle Paul as written for those from the gentiles who had believed. And over and above all of them is the gospel of John”…“But he who was made a suitable minister of a new testament not of the letter but of the spirit, Paul that is, fully preached the gospel round about from Jerusalem even to Illyricum, but he did not write to all the churches he had taught; he wrote only fourteen letters, most of them quite short. A number of people, though, are uncertain about the one written to the Hebrews, inasmuch as it does not seem to verify what he says about himself, namely that he is unskilled in speech. What I say, though, is what my elders have handed down to me, that it is quite clearly Paul’s, and all of our elders accepted it as Paul’s letter. But if you ask me from whom its wording comes, God knows for sure; the opinion which we have heard, though, is as follows: some used to say that it was from Clement, the disciple of the apostles and bishop of Rome, that the letter received the elegance of its Greek, but not its thought; others attributed this to Luke, who wrote the gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. As for Peter, upon whom Christ’s church is being established, he wrote only two letters, about the second of which a number of people are uncertain as well. John too, who reclined upon the Lord’s chest, wrote the Apocalypse too after the gospel; in the former, though, he was ordered to keep silent about what the seven thunders had said. He also wrote three letters, two of which are quite short; some people consider these two doubtful.” – Origen quoted from Rufinus of Aquileia (History of the Church, Translated by Philip R. Amidon, SJ)

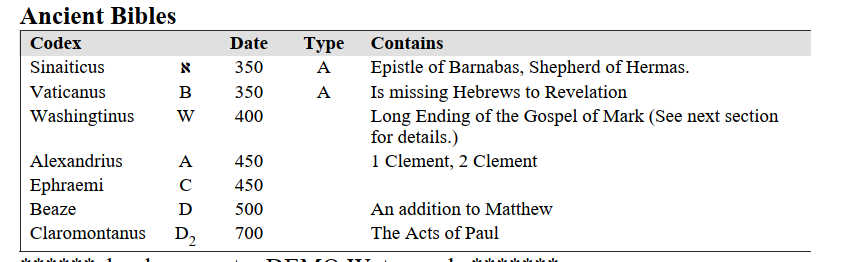

The principal books of the New Testament, the four Gospels, the Acts, the thirteen Epistles of Paul, the first Epistle of Peter, and the first of John, which are designated by Eusebius as “Homologumena,” were in general use in the church after the middle of the second century, and acknowledged to be apostolic, inspired by the Spirit of Christ, and therefore authoritative and canonical. This is established by the testimonies of Justin Martyr, Tatian, Theophilus of Antioch, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen, of the Syriac Peshito (which omits only Jude, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and the Revelation), the old Latin Versions (which include all books but 2 Peter, Hebrews, and perhaps James and the Fragment of Muratori; also by the heretics, and the heathen opponent Celsus—persons and documents which represent in this matter the churches in Asia Minor, Italy, Gaul, North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. We may therefore call these books the original canon. Concerning the other seven books, the “Antilegomena” [disptuted] of Eusebius, viz. the Epistle to the Hebrews, the Apocalypse, the second Epistle of Peter, the second and third Epistles of John, the Epistle of James, and the Epistle of Jude,—the tradition of the church in the time of Eusebius, the beginning of the fourth century, still wavered between acceptance and rejection. But of the two oldest manuscripts of the Greek Testament which date from the age of Eusebius and Constantine, one—the Sinaitic—contains all the twenty-seven books, and the other—the Vatican—was probably likewise complete, although the last chapters of Hebrews (from Heb.11:14), the Pastoral Epistles, Philemon, and Revelation are lost. There was a second class of Antilegomena, called by Eusebius “spurious”, consisting of several post-apostolic writings, viz. the catholic Epistle of Barnabas, the first Epistle of Clement of Rome to the Corinthians, the Epistle of Polycarp to the Philippians, the Shepherd of Hermas, the lost Apocalypse of Peter, and the Gospel of the Hebrews; which were read at least in some churches but were afterwards generally separated from the canon. Some of them are even incorporated in the oldest manuscripts of the Bible, as the Epistle of Barnabas and a part of the Shepherd of Hermas (both in the original Greek) in the Codex Sinaiticus, and the first Epistle of Clement of Rome in the Codex Alexandrinus…As a production of the inspired organs, of divine revelation, the sacred scriptures, without critical distinction between the Old and New Covenants, were acknowledged and employed against heretics as an infallible source of knowledge and an unerring rule of Christian faith and practice. Irenaeus calls the Gospel a pillar and ground of the truth. Tertullian demands scripture proof for every doctrine, and declares, that heretics cannot stand on pure scriptural ground. In Origen’s view nothing deserves credit which cannot be confirmed by the testimony of scripture. – Philip Schaff (History of the Christian Church, Volume II)

The first express definition of the New Testament canon, in the form in which it has since been universally retained, comes from two African synods, held in 393 at Hippo, and 397 at Carthage, in the presence of Augustin, who exerted a commanding influence on all the theological questions of his age. By that time, at least, the whole church must have already become nearly unanimous as to the number of the canonical books; so that there seemed to be no need even of the sanction of a general council. The Eastern church, at all events, was entirely independent of the North African in the matter. The Council of Laodicea (363) gives a list of the books of our New Testament with the exception of the Apocalypse. The last canon which contains this list, is probably a later addition, yet the long-established ecclesiastical use of all the books, with some doubts as to the Apocalypse, is confirmed by the scattered testimonies of all the great Nicene and post Nicene fathers, as Athanasius (d. 373), Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386), Gregory of Nazianzum (d. 389), Epiphanius of Salamis (d. 403), Chrysostom (d. 407), etc. The name Novum Testamentum, also Novum Instrumentum (a juridical term conveying the idea of legal validity), occurs first in Tertullian, and came into general use instead of the more correct term New Covenant. – Philip Schaff (History of the Christian Church, Volume II)

From the middle of the second century great numbers of writings named after the Apostles had already been in circulation, and there were often different recensions of one and the same writing. Versions which contained docetic elements and exhortations to the most pronounced asceticism had even made their way into the public worship of the Church. Above all, therefore, it was necessary to determine (1) what writings were really apostolic, (2) what form or recension should be regarded as apostolic. The selection was made by the Church, that is, primarily, by the churches of Rome and Asia Minor, which had still an unbroken history up to the days of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. In making this choice, the Church limited herself to the writings that were used in public worship, and only admitted what the tradition of the elders justified her in regarding as genuinely apostolic. The principle on which she proceeded was to reject as spurious all writings, bearing the names of Apostles, that contained any-thing contradictory to Christian common sense, that is, to the rule of faith– hence admission was refused to all books in which the God of the Old Testament, his creation, etc., appeared to be depreciated, — and to exclude all recensions of apostolic writings that seemed to endanger the Old Testament and the monarchy of God. She retained, therefore, only those writings which bore the names of Apostles, or anonymous writings to which she considered herself justified in attaching such names, and whose contents were not at variance with the orthodox creed or attested it.

Though Clement of Alexandria no doubt testifies that, in consequence of the common history of Christianity, the group of

Scriptures read in the Roman congregations was also the same as that employed in public worship at Alexandria, he had as yet no New Testament canon before him in the sense of Irenæus and Tertullian. It was not till Origen’s time that Alexandria reached the stage already attained in Rome about forty years earlier. It must, however, be pointed out that a series of New Testament books, in the form now found in the canon and universally recognised, show marks of revision that can be traced back to the Roman Church.

During the Second Century AD, around the year 170 AD, the Muratorian Canon, which is considered the oldest formal list of the New Testament, mentions the 13 epistles of St. Paul and so omits the Epistle to the Hebrews. In that same period, the Paschito Canon mentions St. Paul’s 14 epistles including the Pastoral Epistles as legally acknowledged books. Eusebius also mentions such epistles with St. Paul’s other writings as acknowledged and confirmed legal books. None of the Eastern or Western Church Fathers doubted the authenticity of these epistles or that their author was any other than St. Paul the Apostle. – Fr. Tadros Malaty (Patristic Commentary on First Epistle of Paul to Timothy)

Through tradition, Christians accepted the books of the New Testament as the inspired word of God, before they were canonized by the Church. – Fr. Tadros Malaty (Introduction to the Coptic Orthodox Church)

Although the books of the New Testament were not canonized until the middle of the second century, but through tradition the Fathers of the Church accepted them as the inspired word of God, and many quotations were used in their writings. – Fr. Tadros Malaty (Tradition and Orthodoxy)

Development of the Canon

Scripture was Written by God’s Command

And the Lord said to Moses, Write this for a memorial in a book, and speak this in the ears of Joshua; for I will utterly blot out the memorial of Amalec from under heaven. (Exodus 17:14-15)

Now the Lord said to Moses, “Cut two tablets of stone like the first ones, and I will write on these tablets the words that were on the first tablets you broke. (Exodus 34:1)

Again the Lord said to Moses, “Write these words for yourself, for according to these words I established a covenant with you and with Israel.” So he was there with the Lord forty days and forty nights; he neither ate bread nor drank water. He wrote on the tablets the words of the covenant, the Ten Commandments (Exodus 34:27-28)

Then it shall be, on the day you cross over the Jordan to the land the Lord your God gives you, you shall set up for yourselves large stones and plaster them with lime. You shall write on the stones all the words of this law when you cross over the Jordan, at the time you enter the land the Lord God of your fathers is giving you, ‘a land flowing with milk and honey,’ in the manner the Lord God of your fathers told you. (Deuteronomy 27: 2-3)

Moreover the Lord said to me, “Take for yourself a large new book, and write on it with a man’s pen concerning making a swift plunder of spoils, for it is near at hand. (Isaiah 8:1)

Now therefore, sit and write these things on a tablet in a book, for these things shall be for the time to come, even forever. (Isaiah 30:8)

The word came to Jeremiah from the Lord, saying, “Thus says the Lord God of Israel: ‘Write in a book all the words I have spoken to you. (Jeremiah 37:1-2)

Now in the fourth year of Jehoiakim the son of Josiah, king of Judah, the word of the Lord came to me, saying, “Take for yourself the scroll of a book, and write on it all the words I instructed you against Jerusalem, and against Judah, and against all the nations, from the day I spoke to you, from the days of Josiah king of Judah even to this day. (Jeremiah 43:1-2)

And the Lord answered me and said, Write the vision, and that plainly on a tablet, that he that reads it may run. For the vision is yet for a time, and it shall shoot forth at the end, and not in vain: though he should tarry, wait for him; for he will surely come, and will not tarry. (Habakkuk 2: 2-3)

I was in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day, and I heard behind me a loud voice, as of a trumpet, saying, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last,” and, “What you see, write in a book and send it to the seven churches… (Rev 1: 10-11)