Who Was Dr. George Bebawi and What Happened?

Dr. George Habib Bebawi (1938–2021) was an Egyptian theologian and former professor at the Coptic Orthodox Theological Seminary in Cairo. Educated in Egypt and at Cambridge University, he served in academia and church‑affiliated institutes in the UK and USA. Bebawi became a controversial figure for openly criticizing certain teachings associated with the Coptic Orthodox Church.

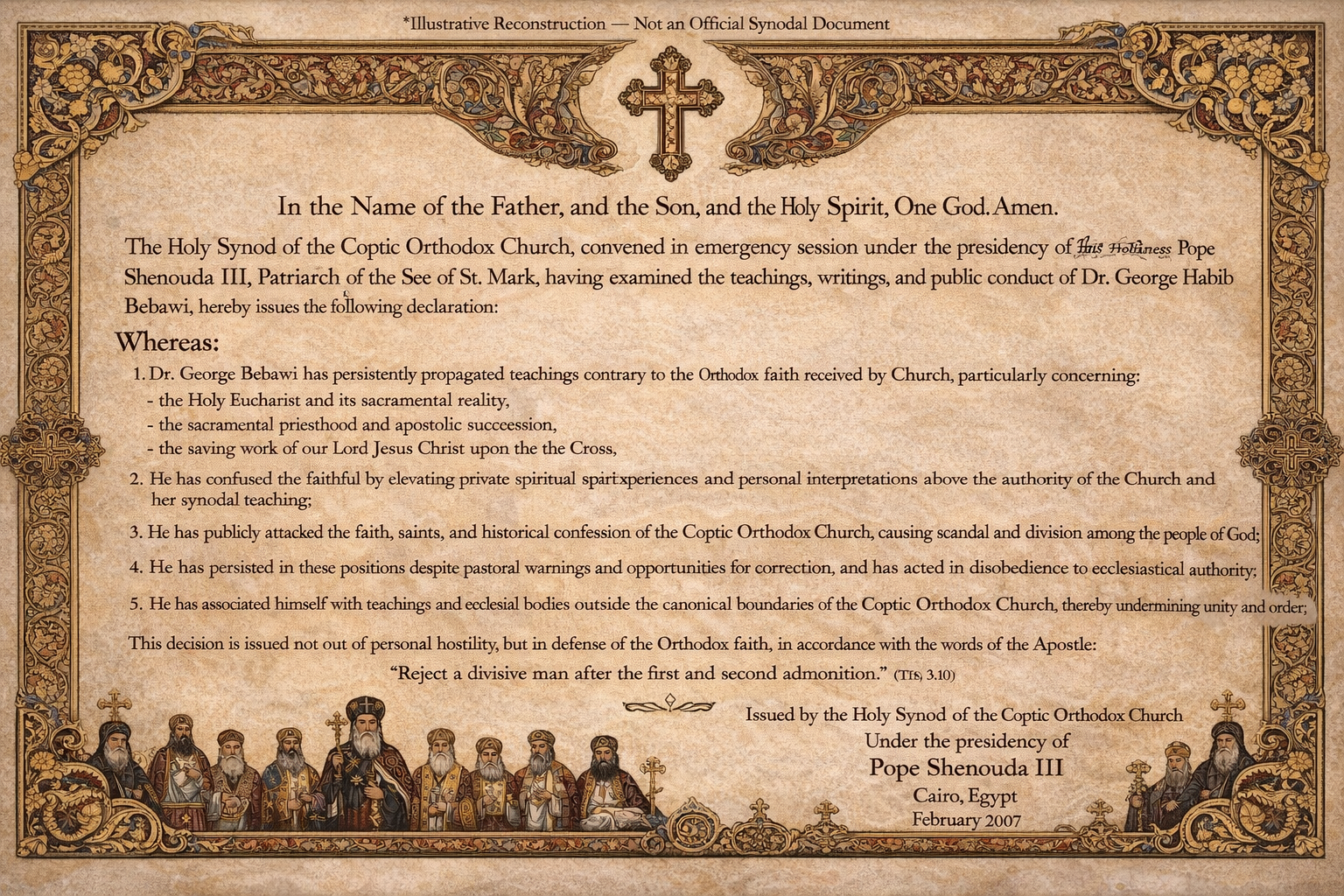

This conflict culminated in an emergency session of the Holy Synod on 21 February 2007, which formally excommunicated Dr. Bebawi from the Coptic Orthodox Church. The Synod’s decision declared that Bebawi was removed and isolated from the Church due to a range of serious violations. Bebawi had also aligned himself with other Christian bodies during the rupture, reportedly even joining the Russian Orthodox Church after his break with the Copts.)

Pope Shenouda III emphasized that the Church’s action was not a personal vendetta but a defense of doctrine: “We are fighting ideas, not persons.”

Theological Errors Cited by the Coptic Church

From the Coptic Orthodox standpoint, Dr. Bebawi propagated several theological and doctrinal errors. A Synodal report presented in 2007 enumerated deviations in faith, summarized below.

1) Denial of the Eucharistic Reality

Bebawi was accused of rejecting the Orthodox doctrine of the Eucharistic change (commonly described as transubstantiation in popular language) and promoting a view closer to Martin Luther’s understanding of the Lord’s Supper (real presence but no change to the bread and wine). For the Coptic Church, this is not a side issue: the Eucharist is central to salvation and the Church’s life.

2) Rejection of the Sacramental Priesthood

He was also accused of denying the continuing sacramental priesthood in the Church, asserting that Christ alone is priest in a way that effectively collapses ordained ministry into non‑sacramental “functional” leadership. The Coptic Orthodox Church regards this as an assault on apostolic structure and sacramental life.

3) Unorthodox Teaching on the Cross and Salvation (Atonement)

According to the Synod’s findings, Bebawi taught that Christ’s work on the Cross was only a symbol of love and not also related to divine justice, thereby “abolishing the concept of punishment.” The Church feared this leads toward a functional universalism (“total salvation”) that diminishes the necessity of faith, repentance, and participation in the sacramental life.

This concern is confirmed by Bebawi’s own words in his published warnings, where he explicitly condemns any understanding of the Cross involving punishment or divine justice:

“Whoever believes that Christ paid the price of sins on the Cross because the Father punished Him or poured upon Him divine justice has departed from apostolic teaching and lost the fountain of salvation.”

Important nuance: The Coptic Church does not endorse a crude “penal substitution” model. But it does affirm that the Cross is not merely a moral example or conquering of death; it is a saving act in which love and God’s judgement are not set against each other, as Bebawi did.

4) Confusion About the Church as “Body of Christ”

Another charge was that Bebawi confused Christ’s personal human body (sinless) with the Church’s “Body of Christ” language, implying that Christians share Christ’s personal sinlessness as though the baptized are beyond ongoing repentance. The Coptic Church rejected this as spiritually dangerous and contrary to Scripture’s insistence that believers still confess sins and grow in holiness.

5) Theosis And the Pope Shenouda Controversy

A major flashpoint was theosis (deification). Bebawi strongly promoted the doctrine and criticized Pope Shenouda III for opposing it, pointing to patristic language (e.g., St. Athanasius: “God became man that man might become god”).

Pope Shenouda III, for his part, was alarmed by formulations that—he believed—blurred the distinction between Creator and creature.

Key point for readers: The controversy was not merely about whether the Church believes in union with God (it does), but about how theosis is articulated and how to preserve safeguards against pantheistic or “creature becomes God by nature” misreadings.

6) Ritual and Ecclesiastical Infractions

Beyond theology, the Synod also cited “ritual violations” and Bebawi’s “movement between different churches.” In canonical terms, joining other ecclesial bodies and teaching outside Coptic oversight can itself constitute schism and warrant discipline.

7) Public Attacks on Church Leadership

The confrontation was not confined to private academic exchange. Bebawi publicly criticized Pope Shenouda III—at times harshly—and the issue escalated in public media. Community councils issued statements supporting the Pope and condemning Bebawi’s perceived transgression. By 2007, the hierarchy viewed him as actively confusing believers and persisting in disputed teachings despite warnings.

How Eastern Orthodox Critics Use the Bebawi Case Against the Coptic Church

Bebawi’s excommunication is often used polemically—especially online—to argue that the Coptic Orthodox Church unjustly excommunicated an “Orthodox” theologian. Common claims include:

Claim A: “They Excommunicated Him for Teaching Patristic Orthodoxy (Theosis, etc.)”

Some Eastern Orthodox commentators argue that Bebawi was simply restoring patristic teaching (particularly theosis) and was punished because Coptic leadership rejected it.

Claim B: “This Proves Pope Shenouda III Was Heterodox”

Critics allege Pope Shenouda III’s cautions about deification and his rhetoric show doctrinal deviation—sometimes attributing it to cultural pressures in a Muslim context.

Claim C: “The Church Silenced an Intellectual (a Modern Inquisition)”

Secular commentators and some church reformists portray the event as an authoritarian suppression of scholarship and open theological discussion.

Claim D: “He Was Condemned Without a Fair Hearing”

Supporters argue Bebawi was not invited to debate or present his defense at the Synod, making the process procedurally unjust.

Refutation:

The “Copts excommunicated an innocent Orthodox theologian” narrative is incomplete and often misleading. A closer look changes the picture.

1) Bebawi Was Not “Pure Eastern Orthodoxy” Across the Board

Even if Bebawi’s emphasis on theosis resonated with Eastern Orthodox priorities, the Coptic Synod accused him of positions no Orthodox Church would regard as acceptable, such as:

- undermining the Eucharistic change,

- denying the sacramental priesthood,

- and teaching a one‑sided view of the Cross that the Church believed undermined repentance and moral seriousness.

If a modern theologian in an Eastern Orthodox jurisdiction denied the sacramental priesthood or rejected the Eucharistic reality, he would not be treated as “sound.” Whatever one thinks about Pope Shenouda III’s rhetoric, these are not minor disputes.

2) The Coptic Church Does Teach Theosis—But With Guardrails

The Coptic tradition includes deeply patristic spirituality and union‑with‑God theology. The Church’s concern is not theosis as such, but formulations that appear to erase the Creator/creature distinction.

So, using Bebawi’s case to claim “Copts deny deification” trades on confusion. The church rejects pantheistic or careless language, not the patristic doctrine of grace‑filled participation.

3) About Process: Church Discipline Isn’t an Academic Symposium

A purely academic standard would demand a formal disputation with the accused present. Ecclesiastical discipline sometimes works differently—especially when a teacher is viewed as publicly scandalizing the faithful, aligning with outside bodies, and refusing submission to the Church’s authority.

That does not automatically prove every procedural decision was ideal, but it does weaken the claim that the action must have been arbitrary or purely political.

4) “Inquisition” Language Is Overheated

The Church’s stated aim was guarding the faithful from confusion. One may argue about severity, but describing any act of synodal discipline as “inquisition” functions more as rhetoric than analysis.

5) Pope Shenouda III’s Cautions Don’t Equal Heterodoxy

Pope Shenouda III’s statements about deification are best understood as a deliberate refutation of an incorrect understanding of theosis—namely, the idea that human beings can become gods by nature rather than by grace. His overall theology and confession remained firmly within Oriental Orthodox boundaries.

6) Eastern Orthodox Praise Does Not Equal Full Endorsement

Bebawi’s acceptance in certain Eastern Orthodox circles does not mean his entire theology was formally evaluated and endorsed. Cross‑jurisdictional sympathy can occur for many reasons (ecumenical hopes, critique of a particular patriarch’s style, etc.) without confirming every disputed teaching.

7) The 2020 Lifting of Excommunication Proved the Point—It Didn’t Erase the Concerns

When Pope Tawadros II lifted the excommunication in 2020, there was notable internal objection and calls for Bebawi to issue a clear apology or clarification. This shows the case was never merely personal; many Coptic leaders believed doctrinal concerns remained unresolved.

Evidence From Bebawi’s Own Words: Why the Excommunication Was Justified

The Road to Emmaus interview with George Bebawi (“With the Desert Fathers of Egypt: Coptic Christianity Today”), conducted after his 2007 excommunication, is frequently circulated by his defenders as proof of his orthodoxy. In reality, the interview supplies direct, first‑person evidence of the very doctrinal and ecclesiological errors cited by the Coptic Holy Synod.

1) Explicit Undermining of the Eucharist and Ecclesial Necessity

In the Road to Emmaus interview, Bebawi describes a practice he was taught and later adopted during a period when he was barred from sacramental Communion.

He recounts being told:

“The time will come when you will receive Communion in your own heart, by intention.”

He adds:

“I never received anything material, nothing to taste or swallow, but every time I did that I used to feel tremendous strength and energy.”

This is not Orthodox teaching. While God is not bound by the sacraments, the faithful are bound to them. Bebawi’s presentation treats inward intention as a standing alternative to the sacrament itself, thereby collapsing the distinction and rendering the Eucharist functionally optional. This directly corroborates the Synod’s charge that he undermined Eucharistic realism and sacramental necessity. To be fair, Bebawi presents this mode of reception as arising from necessity. From the Coptic Orthodox perspective, however, the concern remains that even when framed as necessity, such language risks blurring the boundary between extraordinary economia and ordinary ecclesial life, especially when not paired with a clear insistence on restoration to sacramental and ecclesial communion.

2) Private Mysticism Elevated Above the Church

Bebawi consistently elevates private mystical experience as a theological authority superior to ecclesial discernment. He narrates experiences of clairvoyant insight, visible transfiguration, and spiritual diagnostics as normative indicators of truth. Describing an elder he followed (Fr. Meinas), he writes:

“Before my eyes, his physical presence vanished and he became a flame of fire… The Lord has shown you something in me, but it is also in you.”

Such experiences are not presented cautiously as personal consolation but as epistemic grounds for theology, implying that institutional Orthodoxy is spiritually deficient compared to charismatic insight. Orthodox tradition consistently warns against precisely this substitution of private gnosis for ecclesial authority. The Synod’s concern about spiritual elitism and confusion among the faithful is therefore directly confirmed by Bebawi’s own narrative.

3) Open Rejection of Coptic Christology and Saints

In the interview, Bebawi does not limit himself to internal critique. He explicitly repudiates the historical Christological stance of the Coptic Orthodox Church and its confessors. He states that the post‑Chalcedonian trajectory of the Coptic Church was fundamentally mistaken and portrays its theology as defective:

“The present condition of the Coptic Church – isolated, poor, oppressed, and lacking the richness of the Patristic tradition – is very sad.”

More directly, he asserts that Dioscorus of Alexandria made a serious error in rejecting Chalcedon and implies that this error still defines the Church’s doctrinal weakness. This is not merely academic disagreement; it is a public repudiation of Coptic saints and councils, something no Orthodox Church permits from a theologian claiming to teach in its name.

4) Theosis Framed in Explicitly Palamite, Anti‑Coptic Terms

Bebawi presents deification almost exclusively through Palamite essence–energies language while portraying the Coptic hierarchy as doctrinally ignorant or politically compromised. He openly accuses Pope Shenouda III of attacking deification itself:

“The present Coptic patriarch, Shenouda III, has attacked deification (theosis) as a Byzantine heresy, partly out of his fear of Islam.”

Whether one agrees with his assessment or not, his posture is that of a theologian correcting his own Church from within a Palamite framework that the Coptic Orthodox Church does not share, particularly in its articulation of theosis—despite the Church’s full acceptance of early patristic teaching on participation in the divine life. This Palamite posture, rather than the mere affirmation of theosis itself, is what the Synod regarded as an ecclesiological rupture.

5) Sacramental Objectivism Explicitly Denied

In the interview, Bebawi recounts stories in which sacramental validity appears tied to perceived spiritual purity rather than objective ecclesial action. He also expresses suspicion toward ritual and institutional forms of worship when they are perceived as obstacles to interior awareness of God.

“The more you plunge into symbolism, the more you engage the mind in self‑awareness, rather than in an awareness of God.”

The Coptic Church judged this approach to reduce the sacraments from objective acts of the Church to subjective spiritual experiences, undermining Orthodox ecclesiology.

Why This Interview Weakens—Not Strengthens—His Defenders’ Case

Ironically, the Road to Emmaus interview—often cited to “prove” Bebawi’s Orthodoxy—does the opposite. In his own words, he:

- replaces sacramental Communion with inward intention,

- elevates private mystical experience above ecclesial authority,

- repudiates Coptic saints and councils,

- frames the Coptic Church as doctrinally defective,

- and substitutes sacramental objectivity with spiritual subjectivism.

These are not marginal disputes. They are precisely the kinds of positions Orthodox Churches discipline. The interview therefore does not expose injustice; it supplies first‑hand evidence explaining why the Coptic Holy Synod acted.

When read carefully, the document reveals that Bebawi was not excommunicated for being “too Orthodox,” but for placing himself above the Church he claimed to serve.

Conclusion

George Bebawi’s excommunication cannot be reduced to a simplistic story of “Copts expel an Orthodox theologian.” From the Coptic Orthodox standpoint, he was disciplined for a constellation of serious doctrinal and ecclesiastical violations—especially teachings perceived to undermine the Eucharist, priesthood, repentance, and the meaning of the Cross.

Yes: the case is used polemically by some Eastern Orthodox critics to paint the Coptic Church as anti‑patristic or anti‑theosis. But that portrayal collapses important distinctions, ignores substantial allegations against Bebawi that no Orthodox Church would treat as trivial, and often leans on internet caricatures rather than careful theological reading.

A sober defense of the Coptic Church can admit imperfections in rhetoric and process while still affirming the central point: the Church acted in what it believed was fidelity to the apostolic faith and protection of the faithful.