Introduction

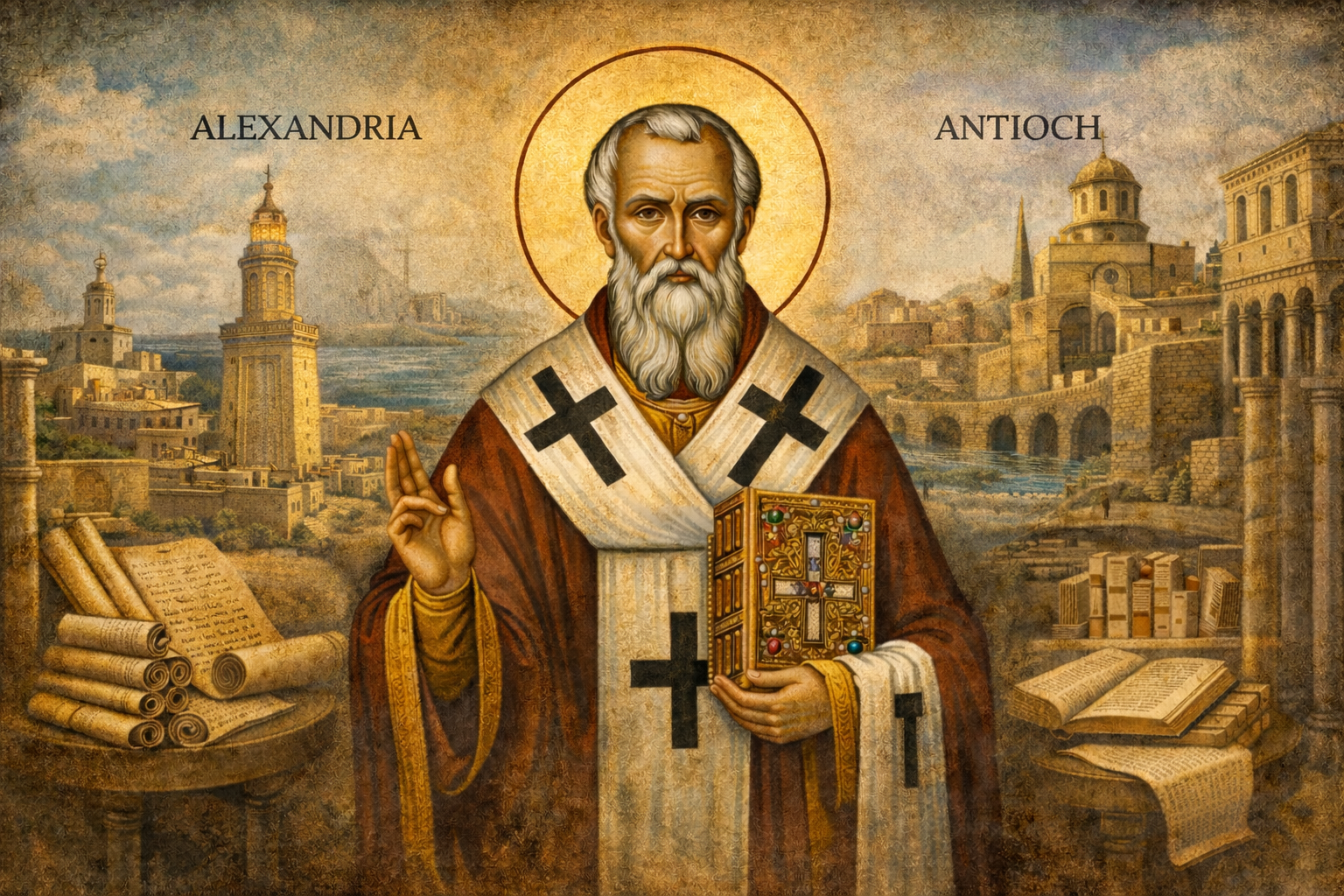

A recurring claim in contemporary Chalcedonian apologetics is that Cyril of Alexandria was, in substance, a dyophysite — that his Christology differs little from what would later be defined at Council of Chalcedon (451). This claim is usually supported by selective quotations in which Cyril acknowledges Christ’s humanity and divinity. The argument is superficially persuasive — and historically careless. This article argues that such claims rest on (1) an imprecise definition of dyophysitism, (2) a failure to understand Cyril’s theological vocabulary, and (3) the systematic removal of Cyril’s statements from their polemical context. When Cyril is read on his own terms, his Christology remains consistently and intentionally miaphysite to the core.

I. Dyophysitism DEFINITION

Dyophysitism, strictly defined, is not the mere acknowledgment of Christ’s divinity and humanity after the incarnation. Every orthodox Christology affirms this. The distinctive marker of Chalcedonian dyophysitism is the confession that Christ exists “in two natures” . This is not an incidental phrase. It is the theological hinge of Chalcedon. Remove “in two natures,” and dyophysitism collapses into a generic orthodoxy shared by Miaphysites, Chalcedonians, and pre-Chalcedonian fathers alike. Retain it, and the difference becomes sharp and historically meaningful.

II. Miaphysitism DEFINITION— and Why Cyril Insisted on It

Miaphysite Christology confesses that after the incarnation, Christ is one incarnate nature of God the Word, a composite reality from two natures, divine and human. Cyril’s insistence on this formulation was not semantic stubbornness. In the Alexandrian theological view, physis (“nature”) could function dangerously close to “concrete subject.” Speaking of Christ in two natures after the union risked re-introducing the very Nestorian duality Cyril spent much of his life opposing. This is not to mention that “in two natures” was the expression used by Nestorians. In other words, language that permitted Christ to be conceived as existing or operating “in two natures” after the union risked reintroducing a duality at the level of personhood, even when formal division or duality of personhood was verbally denied. For this reason, Cyril:

-

Allowed “from two natures” or “of two natures”

-

Rejected “in two natures” after the union

-

Explained repeatedly why the latter was theologically unsafe

III. The Reunion of 433, Doctrinal ToleraNCE, and the Charge of cYRIL’S Change

The “Reunion of 433” refers to the ecclesiastical reconciliation between Cyril of Alexandria and the Antiochene bishops, most notably John of Antioch, following the Council of Ephesus (431). Although Nestorius had been condemned and deposed at Ephesus, a significant portion of the Dyophysite Antiochene episcopate remained estranged from Cyril, suspecting his Christological language to have Apollinarian or Monophysite tendencies and resisting the reception of Ephesus I. This prolonged schism threatened the unity of the Eastern churches and created both theological and political instability within the empire. The reunion was therefore pursued as a pastoral and ecclesial necessity, formalized through a doctrinal agreement known as the Formula of Reunion. The Formula of Reunion does not employ dyophysite language at all; it explicitly utilizes the Miaphysite expression “from two natures” (ἐκ δύο φύσεων), stating:

“We therefore confess our Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, perfect God and perfect man, of a rational soul and body, consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead and consubstantial with us according to the manhood; from two natures, one Christ, one Son, one Lord.”

Thus, far from signaling a Cyrillian shift toward dyophysitism, the Formula of Reunion reaffirms the very language central to Cyril’s miaphysite Christology while allowing continued communion amid churches with terminological differences. Many within the Antiochene tradition continued to employ the dyophysite expression “in two natures,” reflecting their own theological idiom. Cyril’s acceptance of communion with those who used such language constituted toleration, not doctrinal adoption.

This pastoral accommodation, however, quickly generated accusations that Cyril had altered or softened his Christology. His critics failed to distinguish between language he permitted for the sake of unity and the Christology he personally confessed and taught—a misunderstanding he explicitly denied and carefully refuted in his post-433 correspondence. Modern attempts to classify Cyril as a dyophysite merely recycle these same accusations, overlooking the refutations Cyril himself provided in response.

A. Second Letter to Succensus (Letters 44–45)

Cyril writes:

“We do not divide the natures after the union, nor do we introduce two sons… even though the difference of the natures from which the ineffable union came is not abolished.”

Chalcedonian readings typically halt at “difference of the natures” saying Cyril speaks of two “natures” after the union. However, Cyril immediately clarifies that this difference exists conceptually after the union (in theoria), not as two ongoing realities confessed after the union. The confession remains one Christ, one Son, one incarnate [composite] nature. This is Alexandrian miaphysitism with philosophical precision, not dyophysitism.

B. Letter to Acacius of Melitene (Letters 39–40)

Cyril states unambiguously:

“We confess one nature of the Word incarnate, not denying the elements from which the union took place.”

Here Cyril explicitly distinguishes between acknowledging the elements of the union and refusing to speak of Christ as existing in two natures afterward. The former he affirms; the latter he rejects.

C. Letter 46 to John of Antioch

Written precisely to correct misunderstandings, Cyril insists that reconciliation did not entail theological capitulation. Peace did not require adopting Antiochene formulations, nor abandoning Alexandrian ones.

D. Letter 50 to Valerian of Iconium

Cyril explains why he avoids certain expressions altogether:

“We avoid expressions that divide the one Lord Jesus Christ.”

Chalcedonians rightly insist they do not divide Christ. Cyril’s concern, however, is subtler: certain formulas function divisively, even when division is verbally denied. That is why he rejected “in two natures.”

IV. Why the Proof-Texts Fail

Claim: Cyril speaks of Christ’s humanity after the incarnation — therefore dyophysite

Response: Every Miaphysite father acknowledge Christ’s fully humanity. The argument proves nothing.

Claim: Cyril denies confusion — therefore Chalcedonian

Response: Miaphysitism explicitly denies confusion. This is not distinctive.

Claim: Cyril acknowledges distinction — therefore “two natures”

Response: Cyril allows conceptual distinction of “natures” while forbidding dual expression.

The misrepresentation lies not in what Cyril says — but in what Chalcedonians who misrepresent him quietly insert.

Conclusion

The fact inevitably and irrefutably remains that the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and of Ephesus I remains Miaphysite to the core. The Christology of both did not conveniently reconcile with the Dyophysite expressions of Chalcedon. When Cyril’s corpus is taken as a whole—his extensive miaphysite writings, his repeated explanations of his Christological language, and his explicit denials that he ever altered his position—any attempt to portray him as a dyophysite is untenable. Claiming Cyril was a “dyophysite” is conflating what Cyril tolerated for the sake of Church unity with what he embraced as his own Christology and personally taught. Such claims reflect wishful reinterpretation, misrepresentation, or both, driven by the need to align Chalcedon with a theologian whose authority loomed large at Ephesus I– a council miaphysite in expression and intent. Recasting Cyril as a dyophysite thus serves more as a retrospective and convenient justification for Chalcedon’s departure from Cyril’s core expressions, than a historical reality.