Does Palamism Reflect the Faith of the Fathers?

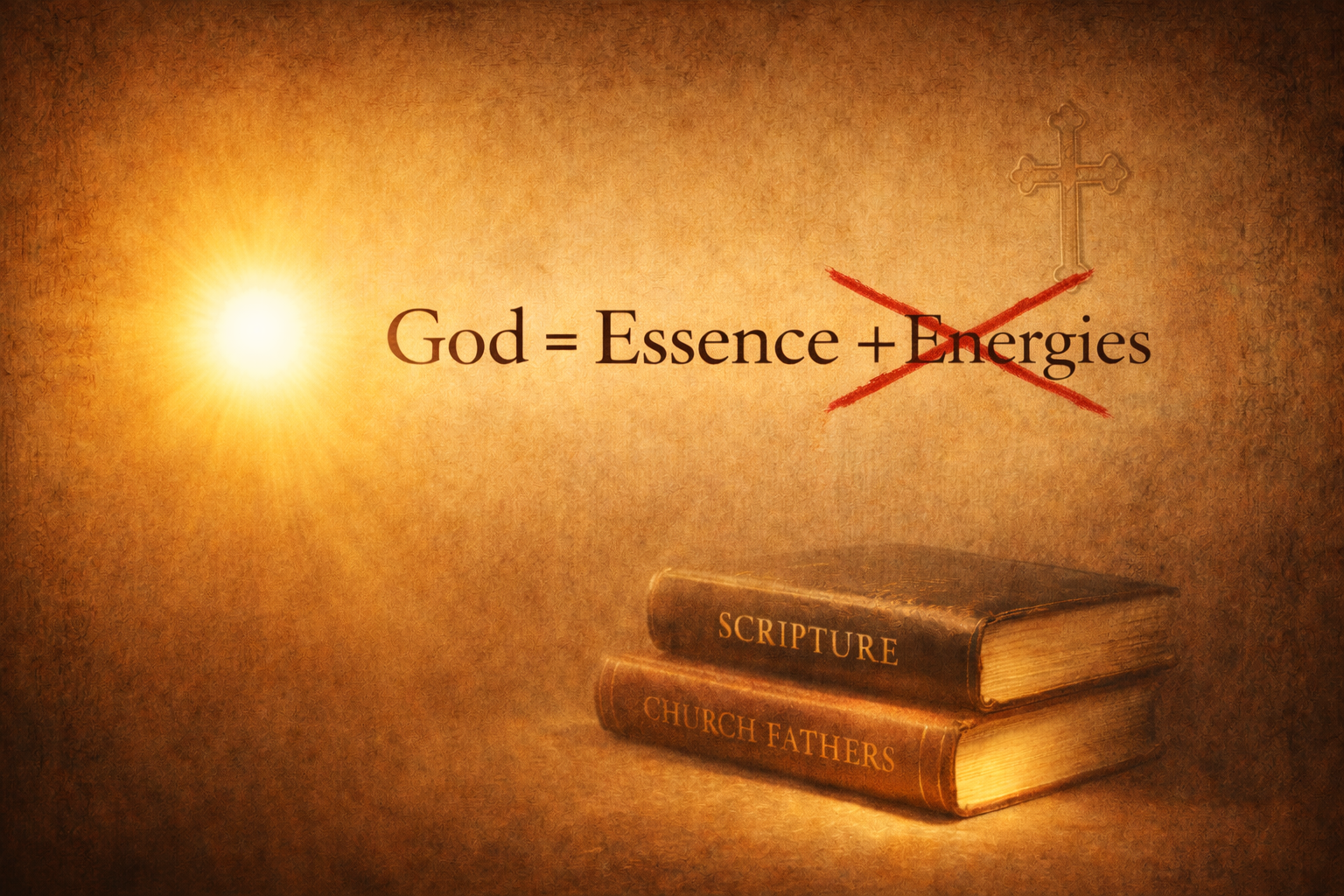

Based on the teaching of Gregory Palamas (14th c.), Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that in God there is a real ontological (pertaining to God’s being) distinction between His essence (οὐσία) and His energies (ἐνέργειαι):

- The essence is utterly transcendent, never seen, never participated in.

- The energies are uncreated operations and manifestations that are really God Himself, yet distinct from the divine essence.

This is not just a way of speaking. It is claimed as a real distinction in God, such that the very definition of God becomes: “God is essence and energies.” — a formula explicitly affirmed by the Palamite councils of Constantinople (especially 1351, often called the Council of Blachernae), which taught that the uncreated light and divine energies are truly uncreated and divine, distinct from the divine essence yet eternally inseparable from it (Synodal Tomos of Constantinople, 1351 — the Council of Blachernae).

This article does not deny the classical patristic language of essence and operation. Rather, the question is theological and historical: did the early Fathers teach an ontological distinction within God’s being, or is this a later reinterpretation of their words?

In this article we will see why from a Scriptural and patristic view, Palamas’s doctrine:

- Arises from a local mystical crisis, not from the Ecumenical tradition;

- Compromises divine simplicity, despite verbal denials;

- Trades on a word–concept fallacy in reading the Fathers;

- Introduces a superior and inferior “God”—essence vs. energies;

- Claims to solve a non‑problem about pantheism;

- Risks undermining orthodox Christology and the doctrine of the Incarnation;

- Re‑opens the Eunomian error in new terminology;

- Culminates in a view of God that is theologically novel and incoherent.

1. Why Palamas Needed the Essence–Energies Doctrine (Historical Origins of Palamism)

The Palamite distinction arose in the context of the Hesychast controversy:

- Athonite monks claimed to see the uncreated light in mystical prayer—the same light of Mount Tabor—and insisted that this was not a mere vision or symbol, but God Himself.

- Barlaam of Calabria objected: if that light is truly God, then either they are deluded, or they claim to see the divine essence—contradicting the doctrine that no one has seen or can see God’s essence (cf. Jn 1:18; 1 Tim 6:16).

Palamas needed to defend three claims simultaneously:

- The monks really saw God,

- What they saw was uncreated,

- Yet they did not see the divine essence.

His solution was to posit uncreated energies:

- distinct from the divine essence,

- identical with “God Himself” in some sense,

- and yet the only aspect of God that can ever be experienced.

Thus the essence–energies distinction is not a neutral clarification of patristic language; it is a 14th‑century construction designed to rescue a specific mystical claim. It was ratified in local councils at Constantinople, but no Ecumenical Council ever defined God as “essence and energies.”

2. Divine Simplicity and the Hidden “Fourth Thing” in God (Does Palamism Divide God?)

Scripture and the Fathers insist that God is simple, not composite. He is the great “I AM” (Ex 3:14), in whom “there is no variableness or shadow of turning” (Jas 1:17). God is not made up of metaphysical parts.

- St Athanasius rejects the notion that God is a compound of quality and essence, insisting that God is “simple essence,” and that making some attribute the defining criterion for His divinity destroys that simplicity. If God’s divinity were “virtue + essence” or “unbegottenness + essence,” God would be composite.

- St John Chrysostom similarly states that God “is simple and has no parts,” emphasizing that we cannot divide God’s being into segments or layers.

If we take divine simplicity seriously, then God’s attributes are distinct from His essence, but cannot be God Himself. We distinguish them in thought; they are not separate “things” in Him.

Palamas’s theology, however, posits:

- an inaccessible essence, and

- uncreated energies that are really distinct from that essence, yet are “God Himself.”

In practice this yields:

- The divine essence;

- The three hypostases;

- A manifold of uncreated energies, which are not the divine essence, are not a hypostasis, and yet are fully “God” somehow.

From a patristic standpoint, however, any suggestion that God is constituted by more than the one simple divine essence was consistently rejected. The Fathers did not teach a further principle in God beyond essence and hypostasis; rather, they insisted that God is simple and incomposite, not made up of distinct ontological layers. Palamas’s treatment of the energies as distinct from the essence—yet still fully “God”—thus introduces what the Fathers never contemplated: a further principle in God that is neither essence nor hypostasis.

Palamas tried to defend himself by analogy with the Trinity: three hypostases do not violate simplicity, therefore essence and energies do not either. But the analogy fails:

- The three hypostases are not three “parts” of God; each is fully the one simple essence.

- The energies, in Palamas, are neither hypostases nor simply conceptual distinctions; they are uncreated actual “somethings” in God distinct from the essence.

The Palamite view is not a mere way of speaking; it amounts to metaphysical division. And once Palamas appeals to the Trinity to justify it, the logic forces a stark dilemma: either the energies constitute a fourth hypostasis, or they introduce a fourth “thing” in God’s being—neither revealed in Scripture nor explained by the Fathers.

3. Misuse of Patristic Language: The Word–Concept Fallacy (Did the Fathers Teach an Essence–Energies Ontology?)

Palamites frequently appeal to the Fathers because they use the words essence and energies. The assumption is:

The Fathers used these words; therefore they meant Palamas’s ontology.

This is a classic word–concept fallacy. Same vocabulary does not entail same doctrine. The Fathers certainly spoke of:

- God’s essence: what God is in Himself, beyond comprehension;

- God’s energies/operations: His works, attributes, and actions toward creation.

But they did not teach that these are two ontological levels in God, with the energies being treated as “God Himself”—in effect a lower ‘deity’ distinct from the higher divine essence, as Palamas argued — In fact the church fathers explained the opposite:

Cyril of Alexandria: No Composition of Nature and Energy

St Cyril explicitly denies that the divine being is composed of “nature and energy” as two different factors:

The divine being is properly and primarily simple and incomposite… one will not venture to think that it is composed out of nature and energy, as though, in the case of the divine, these are naturally other; one will believe that it exists as entirely one thing with all that it substantially possesses. — St Cyril of Alexandria, Thesaurus, PG 75.144A

By contrast, Palamism asserts the opposite: that God is precisely nature and energy understood as really distinct.

Athanasius and Gregory Nazianzen: Attributes Do Not Define or Divide God

The Eunomians claimed that God’s essence is equivalent to unbegottenness, and therefore the Son, being begotten, cannot share the divine essence. The Fathers responded that:

- it is the essence, not a single attribute, that constitutes the divinity;

- to make an attribute the defining essence of God is to turn God into a compound of “quality and essence.”

St Gregory Nazianzen argues that if attributes like immortality, incorruptibility, or unbegottenness were the essence, then God would either have many essences or be composed of many parts. St Athanasius similarly insists that God is “simple essence,” not quality plus essence: “For God, being simple, is not composed of parts, so that one might say His essence is one thing and His quality another” (Orations Against the Arians I.21); and again, “God is simple and not composed of parts … but is what He is, ever the same” (Contra Gentes 3; PG 26.28B–29A).

Palamism repeats the Eunomian mistake with a different term:

- the energies are said to be uncreated,

- “whatever is uncreated is God,”

- therefore the energies, as uncreated, are “God Himself,” over against the essence.

This again treats an attribute (“uncreatedness”) as if it yielded a second quasi‑divine reality.

Energies and Hypostasis

A hypostasis is an individual subsistence—a who. An essence without hypostasis is an abstraction. God is three hypostases of one essence. What, then, is the hypostasis of an energy?

- An energy has no hypostasis of its own; it is the operation of a subject, not a subject.

- As St Athanasius says, the “mind of the Lord” is His will or action towards something, not the Lord Himself.

If the energies are literally “God Himself,” then either they subsist independently of the essence—yielding another deity—or they depend on the essence. But if they depend on something else for their being, they cannot be “God Himself,” because God is self-subsisting. In the former case—where the energies amount to a distinct, lesser deity (as Palamas explains)—Palamas has in effect introduced polytheism, whatever language he may use to soften the claim.

The Fathers treat energies as operations of the one simple God, not as a second ontological principle alongside His essence.

4. A Superior Essence and Inferior Energies (Two Levels of Deity?)

Palamas’s doctrine inevitably introduces a hierarchy within God:

- The essence is the superior, inaccessible level: never seen, never participated in.

- The energies form an inferior, accessible level: the only “God” we ever meet.

But Scripture does not speak of a God we never truly meet. It offers us personal communion with God Himself:

- “We will come to him and make Our abode with him” (Jn 14:23).

- “Do you not know that you are a temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?” (1 Cor 3:16).

Under Palamism, the essence never really enters this communion; only the “energies” do. God “as He is in Himself” is effectively sealed off from the believer. This is structurally very close to Neoplatonic stratification: a hidden One, with mediating emanations below.

5. The Pantheism “Problem”: A Non‑Problem (Does Essence–Energies Prevent Pantheism?)

Palamites justify their doctrine by an appeal to guard against pantheism:

- If we participate in the divine essence, they say, we become God by nature.

- Therefore, to protect the Creator–creature distinction, we must participate in energies, not essence. The energies are “God Himself,” but not His essence.

This logic fails on several levels.

- If energies are “God Himself,” pantheism is not avoided.

If the energies are God, and we truly participate in them, then we participate in God. Merely changing the label from “essence” to “energies” does not avoid pantheism. Either we truly participate in God, or we do not. - Scripture says we are “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4).

It does not say “partakers of uncreated energies that are not the nature.” The Fathers read this straightforwardly: we share in the divine nature through the indwelling Holy Spirit. - Human analogies expose the fallacy.

Communion does not imply identity. Two persons can share the deepest possible fellowship without becoming one essence. A husband and wife become “one flesh” yet remain two persons. Likewise, communion with the divine essence does not dissolve our creaturely nature. - The Incarnation has already answered the fear.

In Christ, the divine and human natures are united hypostatically without confusion or change. If the divine essence can unite with a human nature in the hypostatic union without destroying it, then certainly God can dwell in us and make us partakers of the divine nature without our nature ceasing to be creaturely. The Palamite fear that any communion with the essence would obliterate the creature—that is, alter or absorb its created nature into the divine—is simply contrary to the logic of the Incarnation; and if this did not happen in the hypostatic union, how much less in mere fellowship/indwelling of the Spirit.

Palamas thus constructs a metaphysical firewall to avert an imaginary danger. The Fathers did not feel this anxiety, and so they did not erect an ontological buffer between God and His saints.

6. God’s Omnipresence and the Inescapable Presence of the Divine Essence

All Christians confess that God is omnipresent — He is truly present everywhere. But this raises an unavoidable conclusion: Because God’s essence is divine, His essence must be omnipresent.

So when Scripture declares: “Do you not know that you are the temple of God…?”(1 Cor 3:16), this necessarily means that the divine essence is dwelling in the believers, otherwise it is not the divine omnipresent essence. And when Christ promises: “We will come to him and make Our home with him” (John 14:23), then the divine essence is inevitably abiding in the believer, because God cannot be separated from His divine essence. This leads to the obvious conclusion: the believer inevitably participates in the divine essence — not by nature or comprehension, but by communion and indwelling. Thus, to insist that:

-

God is present,

-

and His essence is inseparable from His energies,

-

yet the believer somehow does not partake of the essence,

is simply self-contradictory. It means the essence is both present and not-present at the same time — accessible enough to dwell in the temple of the believer, yet somehow still inaccessible and distant. This makes no logical or theological sense. Scripture does not say that we commune with divine “energies,” but instead: “our fellowship is with the Father and with His Son Jesus Christ.” (1 John 1:3) and we are “partakers of the divine nature” (1 Peter 1:4)

7. Palamite Defenses Examined (Answering Common Palamite Arguments)

a. “The Energies Are Uncreated, Therefore They Are God” (Palamite Argument Examined)

The Palamite syllogism:

- God’s energies are uncreated.

- Whatever is uncreated is God.

- Therefore, the energies are God Himself (distinct from essence).

The Fathers rejected this way of reasoning in the Eunomian controversy. Eunomius tried to reduce God’s essence to unbegottenness. The response from Athanasius and Gregory Nazianzen was clear:

- No single attribute—unbegotten, uncreated, immortal, immutable—can be made the defining content of the divinity of God.

- To do so is to make God a composite of “essence + quality.”

Even if we grant that God’s operations are “uncreated,” that does not justify elevating them into a second ontological principle in God distinct from the essence. They remain operations of the one simple essence, not another “God.”

b. “God Is Fully Present in Each Energy” (Divine Presence vs. Divine Identity)

Some argue that God is “fully present” in each of His energies, and so encountering an energy is encountering God Himself. Yet presence does not equal identity:

- A person can be fully present in a room without the room being the person.

- A person can be fully present when photographed, but the photograph is not the person himself.

Likewise, God is fully present in His operations; the operations are not thereby “God” as a second thing alongside His essence. To say “the energy is God” because God is present through it is to confuse the subject with His actions. A person is fully present while running, but “running” is not the person; so too, God’s presence in His operations does not convert those operations into a second divine reality.

Moreover, if God is “fully present” in the energies while the essence remains absent, how can He be fully present? Can there be a full presence of God where the divine essence is not present?

c. St Basil and the Eunomian Controversy: What He Did—and Did Not—Teach (Did Basil Teach Palamism?)

Palamites often appeal to St Basil’s dispute with Eunomius. Eunomius accused Basil of blasphemy for saying that we do not know God according to His essence, but according to His works. Palamites insist this is precisely their doctrine (cf. Basil, Contra Eunomium I.14–16; III.2; and Letter 234).

But Basil’s context is crucial. Eunomius claimed that God’s essence is exhaustively known by the concept “unbegotten.” Because the Father alone is unbegotten, and the Son is begotten, Eunomius argued the Son does not share the same essence and is therefore not God. Basil’s response can be summarized:

- God’s essence cannot be reduced to a single concept or predicate.

- Human thought cannot circumscribe or define the divine essence.

- We know God instead by His works and operations, from which we form true yet partial concepts of Him.

St. Paul writes, “Since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made — even His eternal power and Godhead” (Rom 1:20).

By this St. Paul teaches that God is known through His works, not that His works are God. The created order reveals the Creator, but it is never identified with the divine being itself. This is the same point St. Basil makes when he says we know God through His “energies”: he means simply that God’s actions toward creation manifest who He is. Neither St. Paul nor St. Basil ever suggest that these actions or manifestations are themselves God in distinction from His essence. Palamism turns a sound epistemological truth — that God is known through His works — into an ontological duality within God. But Scripture’s meaning is far simpler: creation (God’s works) bear witness to God, not that they are God Himself in addition to His essence.

Thus, St. Basil was refuting Eunomian rationalism, not outlining a Palamite ontology. His point is about knowledge of God’s essence, not internal metaphysics in God, and not fellowship/communion with God. Not an Ontology of “Two Levels” in God:

- Knowledge‑based, not ontological.

Basil explains how we know God, not what God is made of. Knowing God by His works does not imply a second metaphysical layer in God. - Divine simplicity is assumed, not dismantled.

Basil’s entire anti‑Eunomian strategy presupposes that God is not a composite of essence and qualities.

“We Cannot Approach His Essence”: What Basil Meant

Palamites seize on Basil’s phrase that we cannot approach God’s essence and treat it as proof that he denied any communion with the divine essence. Yet in context, “approach the essence” means:

to penetrate and define the divine essence by human understanding.

Basil is saying: we cannot intellectually grasp or circumscribe what God is in Himself, because this is what Eunomius claimed. This is the same truth St Paul expresses: “Now I know in part” (1 Cor 13:12). Our knowledge of God is real yet only partial. Basil was not saying:

we cannot be united to God’s essence.

Indeed, he elsewhere affirms that the Spirit truly indwells believers and that through the Spirit we become God’s temple. The Palamite attempt to read a 14th‑century ontology into Basil’s 4th‑century polemic is thus anachronistic. Basil’s distinction between essence and works is epistemological, conceptual, and simplicity‑protecting, not a precursor to Palamas’s two‑tier God.

Why This Matters for Christology — Basil vs. Eunomius Revisited

Here the stakes become unmistakably clear. Basil’s entire refutation of Eunomius depends on the confession that God is not a composite of essence and qualities. If, as Palamas later taught, God were truly constituted by both essence and “energies” as two really distinct principles in God, then the Eunomian argument would suddenly regain force. Eunomius said: since the Father is unbegotten and the Son begotten, their divinity must differ. Basil replies: no — you cannot make an attribute (unbegottenness) a second ontological principle in God, because God is not essence plus His attributes. It is the one essence that is the criterion of divinity.

But if Palamas were correct — if God were truly essence and energies — then the distinction between what is begotten and unbegotten would once more become an ontological divider. The Son’s “energies,” being manifested through generation from the Father, would constitute a different and inferior participation in the divine reality than the Father’s “unbegotten” mode. In other words, Palamism would reopen the door Basil slammed shut, implicitly conceding to the Eunomians that the Son’s divinity is, in some respect, metaphysically lower than the Father’s.

Thus Basil’s theology does not merely fail to support Palamism — it directly forbids it.

A Christological Consequence: Palamism Undermines the Incarnation and the Deity of Christ

Here the problem becomes even sharper. If God is ontologically a combination of essence and energies, and if the divine essence can never be united to creation or participated in by creatures, then we are forced into one of two conclusions regarding Christ:

- Either the Word did not truly assume human nature in hypostatic union with the divine essence, but only joined humanity to the divine energies;

- Or Christ alone participates in the essence, while the rest of humanity is forever excluded — which destroys the very logic of deification, which is union with God through Christ.

But the orthodox faith confesses that the divine essence of the Word truly united with human nature in the Incarnation. If the divine essence is by definition absolutely inaccessible to creation, then a true Incarnation becomes metaphysically impossible. The Word would either not be fully God in His incarnate state, or His humanity would not be true humanity, but some intermediate mode capable of contacting the divine essence when we cannot. Both options contradict the faith of the Fathers.

Thus the Palamite ontology — though unintended — tends logically either to undermine the Incarnation and compromise the full deity of Christ. These considerations already begin to show that Palamism reshapes not only speculative theology but also the nature of Christian communion with God — a theme explored more fully in Part II.

d. The Inseparability Problem — Yet Only the Energies Are Received

Palamism insists on two simultaneous claims:

- The energies are really distinct from the essence; and

- The energies are eternally inseparable from the essence.

Yet at the same time it insists that:

- Believers participate only in the energies, never in the essence.

This produces an internal contradiction. If the energies are truly inseparable from the essence, then any real participation in the energies must also be a participation—however mysterious—in the divine essence. Otherwise, the word inseparable has been emptied of meaning. Some attempt to answer this with an analogy: the sun’s light is inseparable from the sun, yet we only receive the light without ever touching the solar surface. But this analogy proves the point rather than refuting it. The sun and its rays are not the same thing—the ray is a produced effect flowing from a physical body. By contrast, Palamism insists the energies are not created effects, but are God Himself. If that is so, then communion with the energies is communion with God’s very being; whereas if the energies function more like rays that can be separated in participation from their source, then they cease to be identical with God and become intermediaries instead. There is no middle ground.

But if the energies are in fact separable in the moment of communion, then the doctrine itself collapses, because we would be encountering something that is not God, despite its being called “uncreated.”

Conclusion: Returning to the Simplicity of the Apostolic Faith

In light of the foregoing, the modern formula “God is essence and energies” may be seen not as the teaching of the early Fathers, but as a later theological construction developed in the fourteenth century to address the Hesychast controversy. The Fathers certainly distinguished between essence and operation, yet always as a conceptual and epistemic distinction within the one simple God, not as two ontological principles in Him or as two “levels” of deity. Where Palamism treats this distinction as real within God Himself, the patristic mind insists upon the simplicity of the divine being.

The classical Orthodox faith confessed by the Fathers is beautiful in its clarity:

- One simple, incomposite God, whose essence is beyond comprehension.

- Three hypostases sharing that one essence: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

- Many works and attributes of this one God, by which He reveals Himself and saves us.

Palamism, by contrast, inserts a real ontological division into God Himself and then tries to preserve simplicity by verbal qualification. But if God is essence and energies, then divine simplicity is gone in fact, whatever we may say in theory. Worse still, Christology becomes fragile; once divinity is divided into higher and lower modes, the full deity of the Son is no longer secure.

The Fathers did not need this system. Neither does sound theology. It is enough to believe what the fathers believed: that God’s essence is unfathomable, that His saving works truly reveal Him, and that through Christ and the Spirit we truly share in the divine life—not through an ontological buffer, but through communion with God Himself.