Chalcedonians claim to affirm the Third Ecumenical Council and venerate St. Cyril of Alexandria, claiming to adhere to the Christology of both. But do they? This article is not intended to debate Miaphysite vs. Dyophysite Christology, but rather to examine the internal consistency of Chalcedon’s own claims. It will show that despite their insistence, Chalcedonians affirm neither. Chalcedon presents a reversal of the Miaphysite Christology upheld by Cyril of Alexandria and Ephesus I, while ironically, Chalcedonians manage to claim continuity, affirmation, and fidelity to both Cyril and Ephesus I.

Background for New Readers

To understand the controversy, it is essential to grasp two key terms:

- Miaphysite: The teaching championed by Cyril of Alexandria and affirmed by the third ecumenical Council of Ephesus (431). It means “one nature of God the Word incarnate.” The stress falls on unity: Christ is one, fully divine and fully human, without division.

- Dyophysite: The formula adopted at Chalcedon (451). It describes Christ as existing “in two natures,” divine and human, united in one person. Its defenders argued it preserved Christ’s humanity, while its critics believed it fractured the unity proclaimed by Cyril and the Third Ecumenical Council

- Monophysite: A later term used to describe the belief that Christ has only one nature, with His humanity effectively absorbed into His divinity. Miaphysite Christians reject this label, emphasizing instead that Christ is fully human and fully divine in one united nature.

St. Cyril of Alexandria and Ephesus I: Entirely Miaphysite

Ephesus I was not ambiguous. It confessed without hesitation that Christ is one incarnate nature/hypostasis of the Word. Cyril of Alexandria, the chief defender of Miaphysite Christology, expressed the heart of the council in his famous phrase:

“μία φύσις τοῦ θεοῦ λόγου σεσαρκωμένη” — One incarnate nature of God the Word.

This was not peripheral rhetoric; it was the creed of the council. To revere Cyril while rejecting this expression is to venerate his name but deny his teaching.

Chalcedon’s Shift

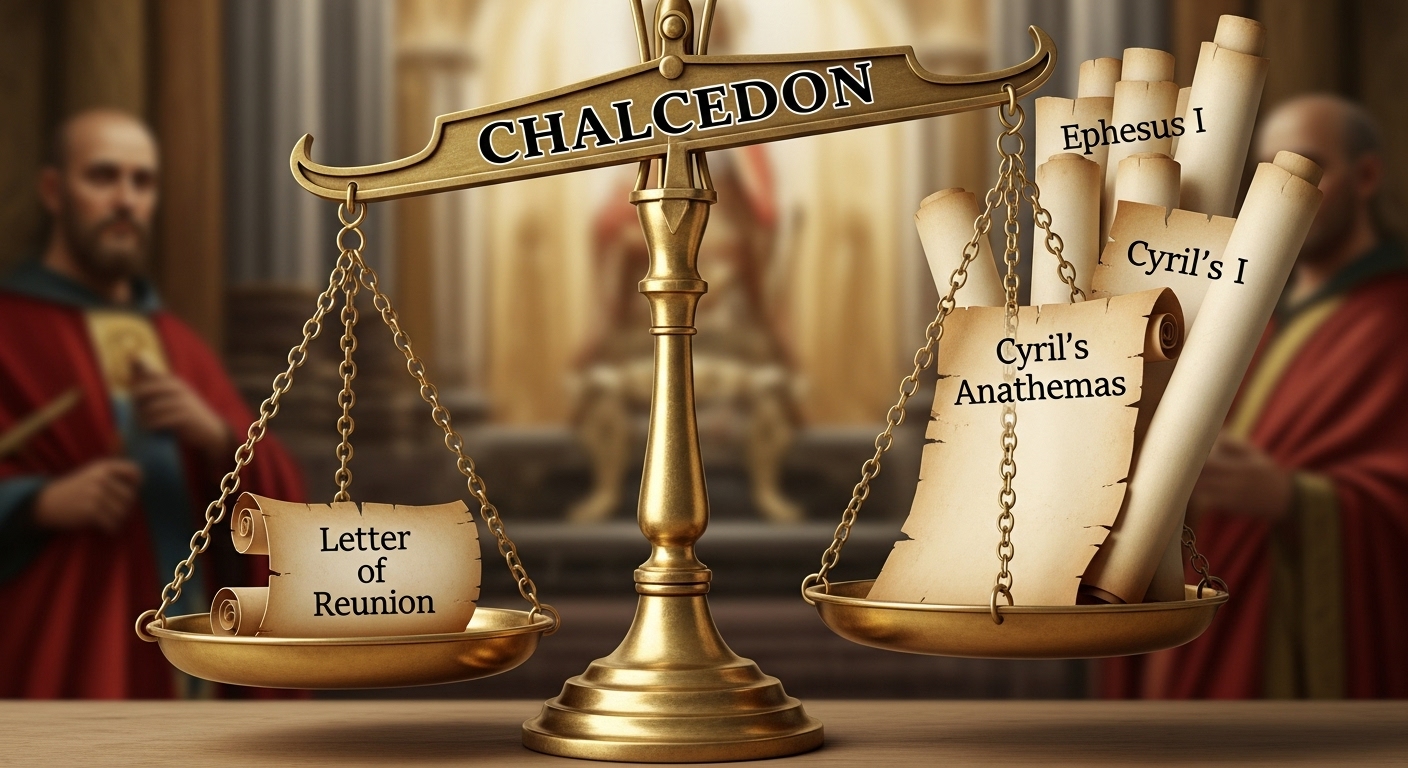

Two decades later, Chalcedon charted a different course. Its definition did not preserve the Miaphysite expressions of Ephesus I, but replaced them with Dyophysite formulae. And to justify this departure, it leaned not on Ephesus, but on another text altogether: the “Letter of Reunion” (433).

The Letter of Reunion in Context

The Formula of Reunion was drafted by Theodoret of Cyrrhus as part of a larger attempt to restore Antiochene bishops—including himself—to communion after they were excommunicated by Ephesus I. It aimed at political and ecclesiastical restoration, not doctrinal definition. Chalcedon took this diplomatic text and elevated it as though it were doctrinal bedrock and used it to deviate from the Miaphysite Christology of Ephesus I—claiming the letter endorses Dyophysite Christology. The letter’s significance must be measured carefully:

- It had no authority to overturn Ephesus I. No letter, however carefully worded, can supersede an ecumenical council.

- It did not teach Dyophysitism. The text confesses Christ as perfect God and perfect man, but never once speaks of two natures after the union. Its language tilts toward accommodation, not replacement. Below is an excerpt of the brief letter:

- Though there is nothing in the letter conceptually objectionable to Miaphysite Christians, the letter is brief and ambiguously lacks both Miaphysite and Dyophysite expressions.

“We confess, therefore, our Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, perfect God and perfect man, of a rational soul and body; begotten before all ages from the Father as to His Godhead, and in these last days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary as to His manhood; consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the manhood.”

Thus Chalcedonians must contend with two problems. First, the Letter of Reunion is not a valid excuse to overturn the Christology of an ecumenical council, even if the letter promoted Dyophysitism (though it did not). Second, since the letter makes no mention of “in two natures”, to claim the letter supports Chalcedon’s Dyophysite definition is not interpretation, but distortion.

Chalcedon’s Reliance on the Letter

Modern scholars such as Pierce, in his commentary on the minutes of Chalcedon, highlight that the council made a conscious choice in its use of sources. Cyril’s most decisive works—the Third Letter to Nestorius and the Twelve Anathemas—were set aside. These were precisely the writings that Ephesus I had upheld as definitive and reinforce Miaphysite Christology. Instead of appealing to them, Chalcedon elevated the Letter of Reunion, drafted by Theodoret, as the foundation for its definition. Pierce observes that this selective treatment was not accidental: it shows the council intentionally dismissed Cyril’s clearest Miaphysite confessions in order to construct a new framework based on the ambiguous reunion letter. The result was a deliberate reshaping of the record, giving the appearance of fidelity to Cyril while quietly replacing his true Christology with something else (that wasn’t even written by him).

Cyril’s agreement to a “reunion” letter does not erase his lifelong Miaphysite confession, nor is it a valid justification for displacing the voice of an accepted ecumenical council. Nothing is. In claiming to honor Cyril, Chalcedon effectively enthroned Theodoret.

Chalcedon’s claim to continuity is therefore untenable. To be consistent, having diverted from the Miaphysite Christology of Cyril and Ephesus I, and pronounced anathemas on the Orthodox Miaphysite Christians who continued to uphold the faith of Ephesus I, Chalcedonians would have had to also condemn both Cyril and Ephesus I outright, but of course they could not do so and still claim validity. Instead, with lip service they continue to affirm both Cyril and Ephesus I outwardly, while condemning those who adhere to them.

The double standard (to say nothing about hypocrisy) is astounding : the Eastern Orthodox later broke communion with Rome because Rome inserted three words—the Filioque—into the Nicene Creed, judging it an unacceptable alteration. Yet Chalcedonians replaced the entire Christology of Ephesus I with another Christology, while continuing to claim continuity and innocence.

Addressing a Common Objection

Some might argue: So what if Chalcedon replaced Miaphysite expressions with Dyophysite ones? Are not both formulas essentially saying the same thing—that Christ is both fully God and fully man? The problem with this objection is that it overlooks what the bishops themselves believed at the time. The bishops of Chalcedon did not treat the formulas as interchangeable, but deliberately set aside the Miaphysite formula in favor of another. The act of rejection and substitution is itself proof of divergence, which led to schism.

A Question of Guarding the Faith

One might ask: What if the Church needed stronger language to guard against Monophysitism? Did it not have the right to clarify and append? Indeed, the Church may supplement earlier explanations—but it cannot replace them. Chalcedon did not build upon Ephesus I; it substituted something else in its place, while insisting nothing had changed. In doing so, it arguably invalidated itself, fell under the anathemas of Ephesus I, and fractured the Church, creating the schism of 451.

This explains why the Fifth Ecumenical Council later attempted to repair the breach—affirming both Miaphysite and Dyophysite expressions in an effort to repair what Chalcedon had damaged.

The Bottom Line

Orthodox Christology, as taught by Cyril and proclaimed at Ephesus I, was Miaphysite. The Letter of Reunion was never a Dyophysite charter, nor did it have the standing to overturn a council. By relying on it, Chalcedon replaced conciliar Christology with a reunion text, then claimed nothing had changed.

Even if one were to imagine that the Letter of Reunion somehow carried the authority of a council—which it clearly did not—the text itself provides no Dyophysite formula. To insist otherwise is an act of self-deception, reading into the letter what it does not say in order to justify a position already taken.

Chalcedonians cannot demonstrate continuity with Cyril and Ephesus I, for their Christology diverged from both. At best, they can acknowledge fragments of Cyril’s teaching and Ephesus I. But they cannot truly claim to affirm both, having diverged from their Christology and while denouncing as heretics those who faithfully adhere to that Christology. That is not fidelity—it is contradiction, and it exposes the revisionism at the heart of Chalcedon.