Introduction

The Council of Chalcedon is often held up as a model of conciliar orthodoxy, correcting the perceived errors of the so-called “Robber Council” of Ephesus II. One of the most damning accusations leveled against Ephesus II was that its leaders, particularly Dioscorus of Alexandria, coerced bishops into signing blank documents or pre-written decrees—so-called “white papers.” These accusations painted the council as illegitimate, its outcomes predetermined, its consensus manufactured.

But what if this charge was not only false—but ironically descriptive of Chalcedon itself?

I. The Original White Paper Accusation Was a Lie

The charge that Dioscorus forced bishops to sign blank or pre-drafted condemnations was a central narrative at Chalcedon. However, when confronted during Session I, several bishops admitted that the accusation was false. Dioscorus, when given the opportunity to question them directly, exposed the slander:

“Did I ever compel you to sign anything against your will?”

The response of many bishops was silence or retraction. The myth of the ‘white paper’ was shattered—not by external refutation, but by the very witnesses who had spread it.

As Richard Price notes in his commentary:

“The allegation that blank sheets were signed was never substantiated, and when questioned, the accusers offered no consistent testimony. The charge functioned more as a rhetorical device than a serious legal claim.” (Acts of Chalcedon, Introduction to Session I)

II. Chalcedon’s Own White Paper Operation

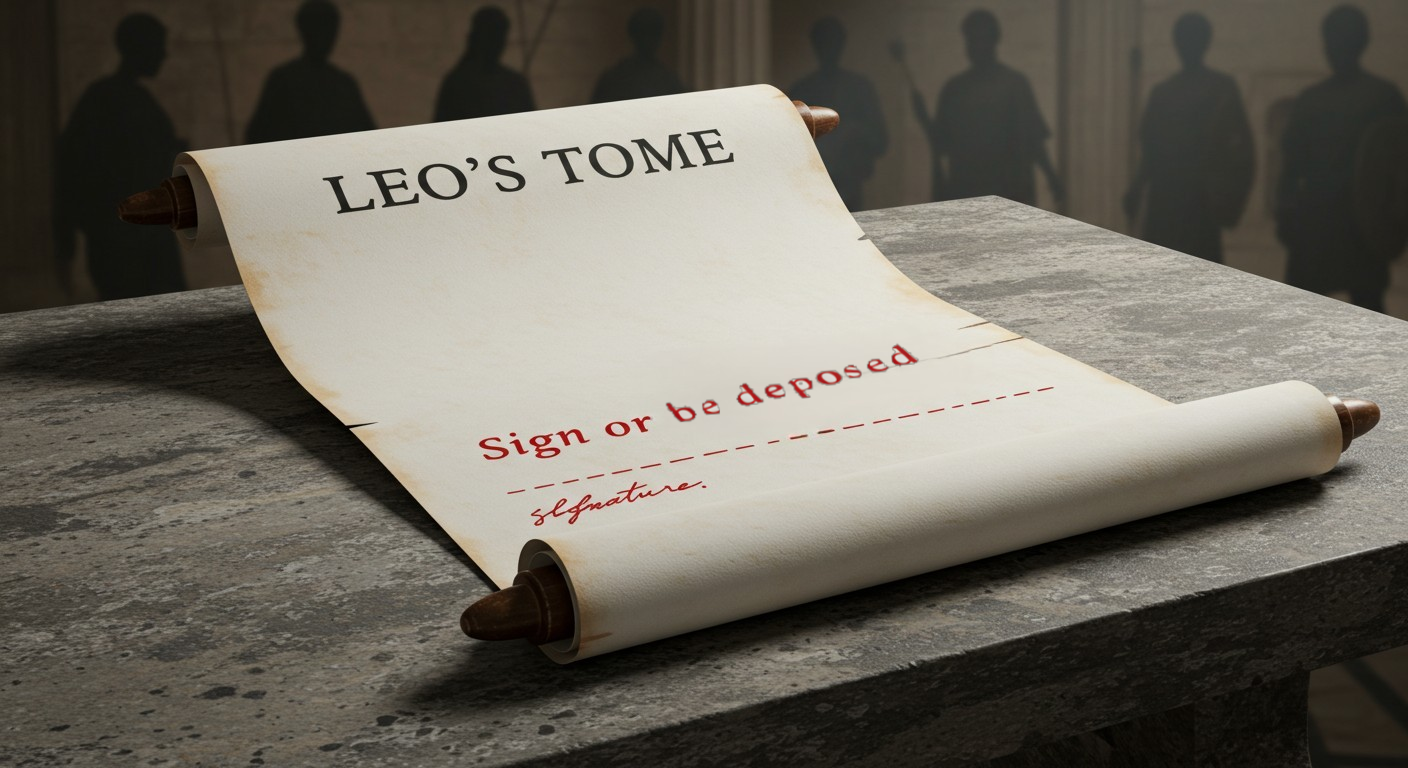

What makes the situation worse is that Chalcedon itself operated precisely in the manner it falsely accused Ephesus II of doing. The council opened not with open discussion, but with the presentation of Leo’s Tome—a pre-written theological document from the Bishop of Rome. And this Tome was not presented as a proposal for review—it was declared orthodox in advance and became the test of communion.

Bishops who hesitated to endorse it were publicly shamed or sidelined. In one striking example from Session II:

“The bishops of Illyricum and Palestine, whose orthodoxy had not been in question, were pressured to approve the Tome of Leo in the presence of the imperial officials.” (Acts, Session II)

And again, in Price’s commentary:

“It is clear that the imperial commissioners and Roman legates were determined to secure affirmation of the Tome. Dissent was unwelcome, and theological discussion gave way to procedural enforcement.” (Introduction to Session II)

III. The Irony of the False Accusation

Thus, the very council that condemned Ephesus II for alleged white papers was itself guilty of enforcing one. Dioscorus was deposed not for heresy, but for refusing to endorse a document whose authority had been established before the council convened. The real “white paper” was Leo’s Tome.

The difference? The accusation against Ephesus II turned out to be slander. The reality at Chalcedon is documented in its own minutes.

And if the perception of coercion was enough to invalidate Ephesus II in the eyes of many, then the documented and systemic coercion at Chalcedon renders it at least equally illegitimate—if not more so. This is not a polemical exaggeration, but a sober application of the same standards.

IV. “So What If the Tome was Imposed if it was Orthodox?”

Some might argue: “Even if Leo’s Tome was imposed, so what? If its theology is sound, then why does the method matter?” This line of reasoning misses two critical points.

- A shift in theological expression:

Even if Leo’s Tome affirms the full divinity and humanity of Christ, its Dyophysite formulation marked a break from the Miaphysite language sanctioned at Ephesus I and used by St. Cyril. For many Eastern bishops, this was not a matter of semantics—it was a matter of fidelity to the accepted theological expression of the Church. This is not to mention that many bishops were concerned about the content of the Tome, not only its expressions. - A breach of ecclesiastical protocol and precedent:

No bishop—not even of Rome—had ever dictated theology to the universal Church without conciliar deliberation. Imposing a single bishop’s text as a precondition for “Orthodoxy” subverted the conciliar model itself. It was not only a procedural anomaly—it was a theological overreach. Orthodoxy, if it is to be universal, must be received, not coerced.

Conclusion

Chalcedon did not correct the procedural flaws of Ephesus II—it perfected them. By beginning with an imposed definition of faith and demanding assent under pressure, it inverted the nature of conciliarity. The council’s legitimacy was founded not on deliberation, but on obedience to Rome and coercion of the emperor. And that is one of the true ecclesiastical scandals of the fifth century.